USF at center of statewide effort to improve health of mothers and babies

For some women, it’s a matter of convenience. For others, the reasons are more pressing – a spouse about to be deployed, an obstetrician’s scheduled vacation, or the availability of a relative to provide childcare.

But whatever the reason, early elective deliveries – deliveries scheduled before a baby reaches a full 39 weeks gestational age without a medical reason – are on the rise. It’s a trend researchers say can lead to serious consequences for babies including severe respiratory distress, learning disabilities, problems breastfeeding, and time spent in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

A trend researchers at the University of South Florida, working with the March of Dimes, the Florida Department of Health and partners around the state, are hoping to change.

PILOT PROJECT TAKES AIM AT RISE IN EARLY ELECTIVE DELIVERIES

In the fall, USF’s College of Public Health and the Lawton and Rhea Chiles Center for Healthy Mothers and Babies at USF received a $100,000 grant from the March of Dimes to establish the Florida Perinatal Quality Collaborative (FPQC). The initiative brings together public and private health care leaders to improve the health of mothers and babies throughout the state.

The collaborative’s first effort, a year-long pilot test of a toolkit designed to eliminate cesarean sections and inductions for non-medical reasons before 39 weeks of pregnancy, officially got under way in six Florida hospitals in January. USF is providing technical assistance and guidance for the initiative.

“In the whole area of prematurity this is something we can have an impact on,” says Dr. Robert Yelverton, clinical associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at USF. “The biggest challenge is changing the long-term habits generated in obstetricians and midwives over the years.”

And a widely-held misconception that a full-term pregnancy lasts nine months.

RAISING AWARENESS ABOUT CRITICAL PHASE IN FETAL BRAIN DEVELOPMENT

A 2009 study in the Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology found that many women do not clearly understand the definition of a full-term pregnancy. About a quarter of moms surveyed considered a baby of 34-37 weeks gestation to be full-term, half defined full-term as 37 to 38 weeks, and 92 percent of women surveyed reported that giving birth before 39 weeks was safe.

“Everyone knows that a pregnancy is nine months, and nine months is 36 weeks,” says Dr. John Curran, associate dean for the USF College of Medicine and chair of the Florida Perinatal Quality Collaborative. But in reality, a full-term pregnancy is closer to 10 months.

“A critical phase of fetal brain development occurs in the last three weeks.”

USF Health’s Dr. John Curran, chair of the Florida Perinatal Quality Collaborative, says a critical phase of brain development happens in the last three weeks of a full-term pregnancy.

According to the March of Dimes, a baby’s brain at 35 weeks weighs only two-thirds of what it will weigh at 39 to 40 weeks – a fact that helps make the case against early elective deliveries in the new 130-page toolkit.

Along with basic brain growth information and information about the complications associated with early elective deliveries, the toolkit, developed in California and endorsed by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM), includes a step-by-step guide for implementing change, ready-made presentations, sample forms, instructions for tracking data, and patient education materials.

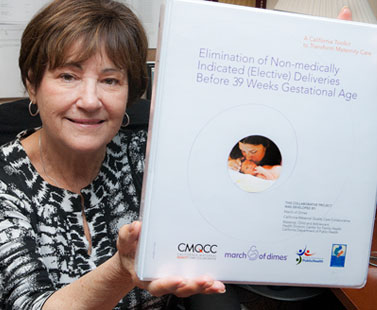

“It (the toolkit) puts resources in the hands of the people who need to create change,” says Dee Jeffers, who, along with Dr. Charles Mahan, helped found the Chiles Center, the state’s only research center specifically focused on maternal and baby health. “Without that, it’s hard to pull it all together. The toolkit gives the rationale and data for making the change.”

NEW RESEARCH = NEW PRACTICE

Brenda Breslow, manager of clinical resource management at St. Joseph’s Women’s Hospital, one of the six participating hospitals in Florida, says the hospital embarked on a week-long information and awareness campaign in the fall. The campaign was aimed at physicians, nurses, childbirth educators, hospital staff and physician practice groups.

For physicians, who have long believed 37 weeks constitutes a full-term pregnancy, the new research represents a change of practice.

“Many (of the physicians) didn’t know how many of these babies were being admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit,” Breslow says. “Once they saw the morbidity data for babies born early without a medical reason, most were open to the change.”

Dee Jeffers holds the toolkit designed to help eliminate cesarean sections and inductions for non-medical reasons before 39 weeks of pregnancy.

That doesn’t surprise Jeffers.

“Practitioners really want what’s best for mothers and babies. It’s a matter of putting the information in people’s hands,” she says.

At Tampa General Hospital, where newborn services are staffed by full-time USF faculty and nurse practitioners, fewer and fewer babies are being admitted to the Muma NICU with complications resulting from early elective deliveries. That’s because of standards put in place two years ago that prohibit the scheduling of deliveries before 39 weeks without a medical indication, says Dr. Lewis P. Rubin, chief of neonatology at USF Health and Tampa General, who oversees all newborn services at the hospital.

“We’ve really taken initiative and been very proactive about preventing early deliveries. If someone tries to schedule an early term delivery without a medical reason, it needs to have further approval.”

While the risk of complications is extremely low at 37 to 38 weeks, “it’s not zero,” says Dr. Rubin, who additionally serves as co-chair of the Florida Chapter of the March of Dimes prematurity prevention campaign.

“The percentage of babies that have problems at the time of delivery are few,” adds Dr. Yelverton. “But when you put all the numbers together, the results are statistically significant.”

That’s something Dr. William Sappenfield, unit director for the Maternal and Child Health Practice and Analysis Unit for the Florida Department of Health, has been studying for the past several years. Even infants born just a few weeks early, his research shows, have higher rates of hospitalization and illness than full-term infants.

SOLUTION COULD IMPACT THOUSANDS OF BABIES

St. Joseph’s Women’s Hospital, like the other Florida hospitals involved in the initiative, each which received a modest grant from the March of Dimes to implement the program, now has a strict policy in place for scheduling inductions and cesarean sections – a policy designed to eliminate early deliveries without a medical reason altogether. Other hospitals participating in the effort include Lee Memorial Health System in Ft. Myers, Plantation General Hospital in Plantation, Santa Rosa Medical Center in Milton, South Miami Hospital in Miami, and Broward General Medical Center in Ft. Lauderdale.

The year-long effort is being duplicated in five states. In total, 25 hospitals in Florida, New York, California, Illinois and Texas – which, collectively, represent about 40 percent of all births in the United States, are testing the toolkit. Effecting change in birth outcomes in these “Big 5” states, according to the March of Dimes, can significantly alter national statistics.

Dr. Lewis Rubin is chief of neonatology at USF and Tampa General Hospital. TGH is not part of the FPQC, but has already implemented standards prohibiting the scheduling of early elective deliveries without a medical indication.

“We have identified a problem that we can fix, and that’s something unique in public health,” says Lori Reeves, state program director for the March of Dimes Florida Chapter. “This one is cut and dry; we have a very concrete solution. Often we don’t see that. This has the scope to impact many thousands of babies.”

And save up to $1 billion annually in the United States, according to the Leapfrog Group, an employer-driven hospital quality watchdog group.

In January, the group released new data finding that thousands of babies each year are electively scheduled for delivery too early, resulting in a higher likelihood of death, being admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit, and life-long health problems.

LONG-TERM ECONOMIC CONSEQUENCES OF PREMATURE BIRTHS

It is an issue, Dr. Curran says, that has “huge economic consequences” for private payers, insurance companies, managed care organizations and Medicaid, which in Florida, covers about half the state’s births.

Leapfrog is working with the March of Dimes and Childbirth Connection, a national advocacy organization, to share information about the importance of every week of pregnancy.

Cecilia Jevitt, a certified nurse-midwife and associate professor in the USF Colleges of Nursing and Medicine, is a member of the Florida Council of Nurse Midwives. She represents the group on the FPQC. Jevitt says it is the long-term effects of an early birth that cause the group concern – for parents and for the state.

“Each year in Florida, more than 200,000 babies are born, and 30 percent of those babies are born by cesarean section,” she says. “Imagine if you could reduce that rate by half. Imagine the savings.”

But Jevitt, who has been in full-scope nurse midwifery practice in the Tampa Bay region for almost 30 years, knows all too well the challenges facing expectant moms today –pressure to return to work, spouses being deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, family members only available to provide childcare at certain times, and the looming fear of losing their job, particularly when a husband has already been laid off.

“We need to improve the economy,” she says. “We need to show women that an early induction may actually waste more time – including recovery time and factors that make breast feeding more difficult for newborns.”

The March of Dimes says scheduled cesarean sections and inductions have become a frequent practice and are viewed as an accepted way to avoid potential complications and problems during labor and delivery. Unfortunately, those good intentions often result in real health problems for a newborn, who may have to spend time in a hospital neonatal intensive care unit, need a ventilator to help them breathe, have trouble feeding because of their early birth or miss an opportunity for the benefits of breast feeding.

A COLLABORATIVE VISION TO IMPROVE PERINATAL OUTCOMES

Dr. Curran, a neonatologist who has cared for thousands of premature babies during his career, and has been involved in the March of Dimes Big 5 State Prematurity Collaborative since 2008, is excited about the toolkit initiative, an initiative that has garnered support from the Florida Obstetric and Gynecologic Society as well as the Florida division of ACOG.

“I really do believe this is going to have a major impact because we have synched it with other initiatives,” he says. “It has major economic implications. This is a collaborative education program implemented in pilot hospitals that will spread around them in concentric circles.”

A program that members of the FPQC hope will be the first of many quality improvement programs focused on the issues of prematurity in the state. Already, the group is looking at a new initiative targeted to newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit.

“The collaborative is working to engage health care institutions across the state – hospitals, clinics, qualified health centers and other professional organizations – to get them all involved in working together to develop a strong vision for improving perinatal outcomes in the state,” says Linda A. Detman, a research associate at the Chiles Center who is coordinating USF’s involvement in the collaborative.

L to r: Leaders of the FPQC initiative include Lori Reeves, Leslie Kowalewski, Dr. Washington Hill, Bill Sappenfield, Cari Crady (Florida state director of March of Dimes), Dr. Robert Yelverton, Dee Jeffers, Linda Detman, Dr. John Curran and Dr. Bryan Oshiro.

Florida March of Dimes official Reeves hopes USF will become the permanent and long-term home for the FPQC.

“USF has the Chiles Center and the College of Public Health. They have the passion to do it, and already have the active participation of several people,” she says. “Not only does USF have a pool of incredible public health professionals, but they have a pool of incredible public health professionals to come.”

Professionals dedicated to improving outcomes for mothers and babies across the state.

– Story by Ann Carney