Therapy offers hope for patients with treatment-resistant depression

For years, Sarah Maloney’s definition of “planning ahead” meant figuring out how to get through another day.

From the time she was 13, Maloney, now 22, struggled with depression – cycling in and out of therapy and trying just about every anti-depressant on the market. Unable to cope or hold a job, she made several attempts on her life.

In March 2011, suicidal and desperate for help, Maloney voluntarily checked herself into Tampa General Hospital’s emergency room. This time, things would be different.

As a patient in the psychiatric services unit, Maloney came under the care of William Upshaw, MD, assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Neurosciences at USF Health. She told him about her years-long battle with depression; about her family’s history of mental illness; about her inability to function; and the anti-depressants that never changed anything.

An alternative treatment option

Dr. Upshaw understood. He told her about a procedure that often works when other treatments have failed. During the procedure, called electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), electric currents are passed through the brain, deliberately triggering a brief seizure. While researchers do not fully understand how ECT works, they do know the seizure activity causes changes in the brain’s chemistry that can reverse the symptoms of certain neuropsychiatric illnesses, especially treatment-resistant depression, during the course of treatment.

For Sarah Maloney, ECT treatments were life changing.

“At first, I thought he was out of his mind; but then he explained it to me after I had calmed down,” Maloney recalls. “It sounded extreme, but at that point I was so desperate not to be depressed or suicidal.”

ECT is the best-known of the neurotherapy procedures – procedures that stimulate areas of the brain using magnetic fields or electrical currents to relieve symptoms associated with certain mental health conditions. ECT was first introduced in the 1930s, and gained widespread use in the 1940s and 1950s. At the time, however, treatments were delivered without anesthesia, using high doses of electricity and often resulting in serious side effects.

Today, ECT is a vastly different and safe procedure using lower doses of electricity administered under full anesthesia. According to Jamie Winderbaum Fernandez, MD, assistant professor and chief of the USF Electroconvulsive Therapy Program at Tampa General Hospital, the results are indisputable.

“ECT is unmatched for short-term relief of major depression. It gets people better when nothing else has,” she says. “There is nothing more satisfying than seeing people get their life back.”

Before consenting to the treatment, Maloney spoke to patients on her floor. “They told me it was great,” she says. And she spoke at length with her boyfriend; her sisters, one, a physician; her father, a nurse; and her mother, a nursing student. “They convinced me it was extremely safe and extremely humane. I was scared, but confident.”

Carefully controlled

ECT patients typically undergo an initial acute series of nine to 12 treatments administered three times a week over three to four weeks. After the initial acute phase, treatment is carefully tapered off over several months. Occasionally, patients will come back for infrequent treatments, called maintenance or continuation ECT, to maintain the benefits they received during treatment.

During the procedure, which lasts about five minutes, the patient is given anesthesia to sleep as well as an intravenous muscle relaxant to paralyze the body. Stimulating electrodes are carefully placed on the scalp, leads are placed on the forehead and neck to monitor brain activity, and a blood pressure cuff, which restricts the flow of the paralytic to the foot, is placed on the lower leg, allowing the treatment team to monitor motor seizure activity. Next, a brief electrical charge is applied to the scalp inducing a seizure that lasts about a minute and is accompanied by a release of chemicals from neurons in the brain. Within about 20 minutes, the patient awakens.

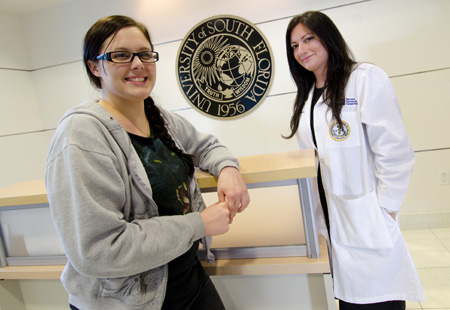

Maloney with Dr. Jamie Winderbaum Fernandez, chief of the

USF Electroconvulsive Therapy Program at Tampa General Hospital

For Maloney, the results were near-immediate.

“I was exhausted, but felt mentally better after the first treatment,” she says. “The deep pit in my stomach and heavy feeling in my chest that I had since I was 13, were gone. I wanted to live.”

Dr. Fernandez had seen it before. During the course of her professional career she has administered more than 1,000 ECT treatments. “I have literally seen it bring people back to normal life after years spent coping with debilitating, chronic mental illness,” she says.

Even so, ECT treatment does have side effects, such as disorientation following the procedure, short-term memory loss and physical side effects including nausea, headache and jaw pain.

The treatment’s effectiveness is contingent on continuation therapy – antidepressants or other medications and/or psychological counseling. “You must do something to sustain the benefit,” Dr. Fernandez stresses.

New service at Tampa General

Dr. Fernandez joined USF Health in 2008 after receiving her medical degree from Cornell University Medical College and completing a residency in adult psychiatry at Stanford University Hospital and Clinics. She holds a Master of Science degree in Medical Sciences with a concentration in Clinical and Translational Research. She is board certified in adult psychiatry and certified in ECT.

Despite having a large psychiatry practice, Tampa General Hospital had no ECT service when Dr. Fernandez came on board. Convinced of the need and aware of the benefits, she teamed with her department chair, Francisco Fernandez, MD, and worked with her colleagues, Dr. Upshaw, Patrick Marsh, MD and Michael Bengtson, MD, to lobby TGH to make the treatment available.

By September of 2010, the treatment was being offered at Tampa General Hospital. Since the service began, Dr. Fernandez estimates that she and her colleagues have administered about 1,200 ECT procedures to patients, many high-functioning adults who have battled depression for years. “There is a tremendous need for it in the area,” she says of the growing practice.

Candidates for ECT range in age from 18 to over 100 years, and suffer with conditions ranging from major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia to catatonia, Parkinson’s disease and delirium. Some, Dr. Fernandez explains, have medical co-morbidities that preclude them from being on medications such as lithium. The treatment can be safely administered in all stages of pregnancy, and in fact, is considered safer than medications in the first trimester.

A new lease on life

For Maloney, the treatments have been life-changing. Today she is a full-time office secretary, lives in her own apartment and is planning a wedding with the boyfriend who stood by her side through it all. She has completed 25 ECT treatments since she first checked herself into Tampa General Hospital in March 2011. Her treatments now are scheduled monthly.

Maloney is eager to talk about her experience. “I want to take away the feeling of embarrassment that people with mental health problems have. I want to help take away that stigma.”

But most of all, she is eager to plan her future.

“For the first time in my life I am actively planning a future,” she says. It’s exciting to have a life and want to live it.”

Story by Ann Carney. Photos by Eric Younghans/USF Health Communications

____________________________________________________________________

Improving the Symptoms of Depression and other Neurological and Mental Health Conditions

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is one of four neurotherapy procedures – including transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), deep brain stimulation (DBS) and vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) – offered at USF Health’s Neurotherapies Clinic at Tampa General Hospital. The procedures stimulate brain cells electrically, rather than with medications, to treat depression and other mental health conditions.

TMS — Using pulsed magnetic fields, Neurostar TMS therapy stimulates the part of the brain thought to be involved with mood regulation. The short, non-invasive, non-systemic procedure is performed on an outpatient basis and typically consists of five treatments per week over a four- to six-week period. The treatment is an effective alternative for patients who cannot tolerate the side effect associated with anti-depressant medication. TMS therapy does not have the usual side effects including weight gain, sexual dysfunction and nausea. Patients are awake and alert throughout the entire 37-minute procedure, and can transport themselves to and from treatment.

DBS — Using a surgically implanted medical device, similar to a pacemaker, DBS delivers carefully controlled electrical stimulation to target areas of the brain, continuously or intermittently, to treat neurological disorders such as essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease (PD) and anxiety disorders such as obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). The stimulation is delivered to areas of the brain that control movement, blocking the abnormal nerve signals that cause tremor and PD symptoms and helping reduce the symptoms associated with OCD.

VNS — Approved for use in treatment-resistant epilepsy and treatment-resistant depression, VNS therapy uses an implanted pacemaker-like device to deliver mild, intermittently pulsed signals to the left vagus nerve, which in turn activates various areas of the brain. Stimulation to the left vagus nerve has been shown to induce widespread effects in areas of the brain thought to be responsible for seizures and mood disorders. The treatment is approved as an adjunctive therapy for reducing the frequency of seizures in adults and adolescents over age 12, and as an adjunctive, long-term treatment for chronic or recurrent depression for patients 18 years and older who are experiencing a major depressive disorder and have not had adequate response to other anti-depressant treatments.

To learn more about the USF Neurotherapies Clinic or to make an appointment, visit www.health.usf.edu/medicine/psychiatry/neurotherapy or call 813-259-0920.