Symposium participants optimistic about finding first treatment for Friedreich's ataxia

With all the significant scientific advancements presented, at the end of the symposium it was the people with Friedreich’s ataxia who gave the research meaning and value.

They were people like Holly LeBlanc, who for eight months traveled back and forth from Holland, MI, to USF to participate in a pilot clinical trial testing effects of the drug varenicline on neurological symptoms of Friedreich’s ataxia. She was back again August 26, with her mother and service dog Delsie, to attend the second annual scientific symposium hosted by the Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance (FARA) and the USF Ataxia Research Center. Building on last year’s momentum, the “Cultivating a Cure” symposium drew scientists, clinicians and patients from across the country.

L to R: Holly LeBlanc, Mary Vida, Nygel Lenz and Kyle Bryant particpated in the symposium’s patient panel discussion on living with Friedreich’s ataxia.

“I consider USF my home away from home. The zest of Dr. Zesiewicz and her team to find a cure and treat me as a whole person has been amazing,” said LeBlanc, 37, who was diagnosed with Friedreich’s at age 24, after being misdiagnosed with another ataxia.

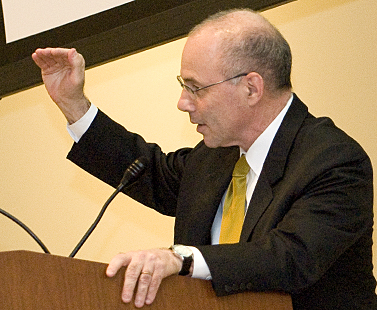

LeBlanc, who has a master’s degree in counseling, joined three other patients – Kyle Bryant, Nygel Lenz and Mary Vida – for a panel discussion moderated by Stephen K. Klasko, MD, MBA, CEO for USF Health and dean of the College of Medicine.

The patients spoke about their challenges, determination and optimism that the race would be won to find a first treatment for Friedreich’s ataxia, a rare, degenerative neuromuscular disease marked by slow, progressive loss of balance, coordination and muscle strength. Friedreich’s can also impair speech, vision, hearing and lead to diabetes and potentially life-threatening cardiac disease. There is no cure.

In the last decade, researchers have made significant advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms of Friedreich’s ataxia and have developed cell and animal models to improve testing of drug candidates. Today, more than a dozen promising investigational drugs with various approaches to treatment are in the clinical trial pipeline.

USF Health’s Dr. Stephen Klasko said significant advances in research toward finding treatments for FA had been made since last year’s scientific symposium.

“The pressure is on, but your courage and optimism makes us want to redouble our efforts,” Stephen K. Klasko, MD, MBA, CEO for USF Health and dean of the USF College of Medicine, told the patients. “We’re energized, not satisfied, by the progress that has been made toward finding a treatment and cure.”

Jennifer Farmer, executive director of FARA, and Ron Bartek, president and co-founder of the organization, spoke about progress nationwide in the research and management of Friedreich’s ataxia. FARA has nurtured powerful public-private partnerships – with government agencies, academic medical centers like USF Health, the pharmaceutical industry and other non-profit patient advocacy organizations – to bolster its pursuit of translational research.

“Building an extensive support network is absolutely essential to moving forward the research that will find treatments for Friedreich’s ataxia,” Farmer said.

Jennifer Farmer, executive director of the Friedreich’s Ataxia Research Alliance, gave a national overview of treatment approaches in the clinical trials pipeline.

Among the featured speakers was Joel Gottesfeld, PhD, professor at The Scripps Research Institute Department of Molecular Biology. Compounds developed by Gottesfeld’s team – histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors – reversed in cell culture the genetic defect that prevents production of the protein frataxin in those with Friedreich’s ataxia. Inadequate levels of frataxin lead to degeneration of both the nerves controlling muscle movements in the arms and legs and the nerve tissue in the spinal cord.

Partnering with FARA and pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies, Scripps researchers have been “working to create molecules that are more active inhibitors of histone deacetylase,” Dr. Gottesfeld said. “We believe we’re on the right track.”

Recently RepliGen Corp. licensed one of the molecules, RG2833, an inhibitor of histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC-3), to develop for treatment of inherited neurodegenerative diseases including Friedreich’s ataxia. In neuronal stem cells cultivated from skin cells of patients with Friedreich’s, that molecule restored frataxin to near-normal levels – 90 percent of that in unaffected neuronal stem cells, Dr. Gottesfeld said.

One of the HDAC inhibitor molecules discovered by Dr. Joel Gottesfeld’s team at The Scripps Institute is being developed as a treatment for inherited neurogenerative diseases, including FA.

Theresa Zesiewicz, MD, professor of neurology and director of the USF Ataxia Research Center, provided an update of her studies testing the smoking cessation drug varenicline as a potential treatment for symptoms leading to frequent falls in patients with Friedreich’s ataxia.

In a retrospective study of 21 patients with all types of ataxias, 25 percent of all patients and 38 percent of those with spinocerebellar ataxias demonstrated improvement with varenicline, Dr. Zesiewicz reported. In a pilot clinical trial, two out of three Friedreich’s patients improved on the drug. A complicating factor was that the drug’s side effects, including tremor and nausea, were intolerable for some participants, she added.

The clinical results – showing some patients with Friedreich’s ataxia clearly responding to varenicline and a percentage who experienced medication side effects — led Dr. Zesiewicz and her co-investigators back to the laboratory. They wanted to try to understand the effects of partial nicotine acetylcholine agonists on Friedreich’s.

Varenicline acts at various receptors affected by nicotine, but it’s unclear exactly which receptors are targeted. “It’s likely the ability of varenicline to improve ataxia is due to a combination of mechanisms,” Dr. Zesiewicz said. “We have to figure out where and how the drug is working in the brain or other parts of the nervous system.”

Ron Bartek, president and co-founder of FARA, said that the pharmaceutical industry is showing increasing interest in developing drugs for rare diseases.

To answer those questions, Dr. Zesiewicz turned to colleague Lynn Wecker, PhD, USF distinguished research professor of molecular pharmacology, physiology, psychiatry and neurosciences. Dr. Wecker has been studying nicotinic receptors in the brain for some 30 years, with an emphasis on investigating the brain chemistry of neuropsychiatric disorders like schizophrenia, depression and addictive behaviors. Now, supported by funding from the Florida Center of Excellence for Biomolecular Identification and Targeted Therapeutics at USF, she’s using a rat model for spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 to test the effect of varenicline on ataxia.

The animal model may help researchers better define which receptors are involved in ataxias, including Friedreich’s. “If we can identify those targets, we can design other drugs, with fewer side effects (than varenicline), to hit them,” Dr. Wecker said.

L to R: Symposium speakers included Dr. Joel Gottesfeld, Dr. Theresa Zesiewicz, Dr. Lynn Wecker, Dr. Clifton Gooch and Dr. Guy Miller.

Also speaking at the symposium was Guy Miller, MD, PhD, CEO and chairman of Edison Pharmaceuticals. Edison focuses on developing drugs to treat mitochondrial diseases that share a common feature – defects in how the body makes and regulates energy metabolism. The loss of function of the protein frataxin in Friedreich’s patients has been associated with the impaired ability of mitochondria in nerve cells to make energy.

Edison’s researchers have studied two rare mitochondrial diseases — Leigh’s disease and Leber’s hereditary optic neuropathy (an aggressive inherited form of vision loss) — as a bridge to understanding more about Friedreich’s ataxia, Dr. Miller said. Dr. Miller described how one drug candidate – a broader, more potent derivative of the antioxidant CoQ10 – has shown benefit without adverse effects in young children with genetic mitochondrial diseases. Over the next year, Edison plans to move forward in collecting data about the drug’s potential benefit for patients with Friedrich’s, another energy impairment disease.

No one drug will be the answer to Friedreich’s ataxia; it will likely take a combined approach, Dr. Miller said. “It may require a cocktail like an HDAC inhibitor combined with a drug having the ability to mitigate oxidative stress … that will stop this disease in its tracks.”

There is reason for cautious optimism, he added. “We’re very much closing in on this disease…. Understanding the specific mechanisms of action and developing drugs for them are going to open up new vistas (for treatment) extending beyond Friedreich’s ataxia to neuropsychiatric diseases, epilepsy and a whole host of other diseases that involve interruptions of energy metabolism.”

Holly LeBlanc and Kyle Bryant

The patient panel at the close of the symposium echoed the sense of urgency to find a first treatment for Friedreich’s ataxia.

Panelist Kyle Bryant, diagnosed with Friedreich’s at age 17, recently competed as a member of Team FARA in the Race Across America, a relay-style endurance cycling event. His four-member team, which included two cyclists with Friedreich’s riding three-wheeled bicycles, finished first place in the four-person open division.

“We’ve proven to ourselves and everyone else that, together, there’s nothing we cannot do,” Bryant told the audience. “We’re going to cross that finish line and beat this disease…. because, are you kidding, we just rode 3,000 miles in eight days!”

LeBlanc, who participated in a FARA-sponsored clinical trial at USF, said her service dog Delsie allowed her to walk for an additional four years.

In his closing comments to an energized audience, Clifton Gooch, MD, professor and chair of neurology, acknowledged the philanthropists, researchers, academic institutions and passionate leaders required to advance a rare disease from a point of little or no understanding to a stage where promising treatments are on the horizon.

“But, most of all,” Dr. Gooch said, “it takes patients and those who support and care for them who will marshal the resources needed to make things happen.”

At the pre-symposium poster session, Jeannie Stephenson and Seok Hun Kim of the USF School of Physical Therapy & Rehabilitation Sciences presented a case study evaluating gait and balance in FA.

Story by Anne DeLotto Baier, and photos by Eric Younghans, USF Health Communications