Extreme Exercise: How much is too much?

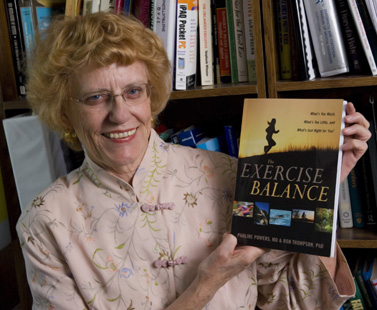

USF psychiatrist Dr. Pauline Powers says finding the right balance of exercise can be difficult in a society that has shifted the focus of exercise from health to appearance.

University of South Florida psychiatry professor Pauline Powers, MD, is all for exercise being part of a healthy lifestyle. In fact, she manages to fit time with a personal trainer twice a week and YMCA aerobics into her hectic schedule.

But, she also wryly notes that working out won’t prevent death. In fact –like too much of any good thing – too much exercise can make you sick, Dr. Powers said.

“There’s a real emphasis on the obesity epidemic in today’s society. The message that tends to come across is that everyone is overweight and under-exercising,” she said. “While not enough people are exercising and too many people are overweight, it is not true that the majority is overweight and not exercising. We just don’t really hear much about the dangers of extreme exercise.”

Dr. Powers co-authored the recently published book The Exercise Balance with psychologist colleague Ron Thompson, PhD. Both specialize in the treatment of eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia and severe obesity.

The book discusses both ends of the exercise spectrum — from addictive exercisers who push their bodies to extremes to meet unrealistic standards for thinness or “fitness” to sedentary people who need to be more active. Using a combination of clinical studies and real-life examples, the authors offer practical guidelines for creating individualized, balanced exercise plans, including those tailored for different age groups and people with chronic illnesses.

Dr. Powers, past president of the National Eating Disorders Association, became interested in exercise addiction because many patients she treats have developed a dysfunctional relationship between exercise and eating. “At least half of the people with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa started with too much exercise,” she said, “and the more compulsive the exercise the greater the psychopathology of their eating disorders.”

Ironically, Dr. Powers said, while the debate about obesity grabs the headlines, increasing numbers of people are also engaging in excessive exercise – spending hours a day at the gym or training for ultramarathons that tax their endurance in extreme temperatures and terrain.

The health hazards of a sedentary lifestyle, including hypertension, diabetes and heart disease, have been widely publicized, but excessive exercise has its own set of medical consequences, she added. These include stress fractures, musculoskeletal injuries, cardiovascular complications, and, among women who train excessively, a condition known as female athlete triad, which is characterized by dieting, menstrual irregularity, and bone loss.

Some people erroneously believe “if some exercise is good, then more must be better,’ much like ‘if thin is good, thinner is better,’” Dr Powers said. But, among even competitive athletes who train more intensively than the average American, too much exercise may lead to “overtraining syndrome” or “staleness” – a condition marked by fatigue, weight loss, depression, and even a decrease in sports performance.

“More exercise does not necessarily improve athletic performance, nor does reducing weight or body fat,” she said. “It might if an athlete is not training enough, or if they’ve become overweight. But, usually that’s not the case, and it’s factors like genetics and personality traits that make the competitive difference.”

Most people (who are not competitive athletes) need to set reasonable and realistic goals for health and fitness, taking into account physical factors, such as their body type and muscle mass, and life circumstances like age and health status, Dr. Powers said. “My neighbor, who is a triathlete, wants me to run a marathon with her. Well, I’ll never be able to run a marathon. I can run 2 miles, but not a marathon.”

So, how do you know if you’re just embracing physical fitness or overdoing exercise? A big indication is if the intensity of exercise starts interfering with your work, school or relationships, Dr. Powers said. For instance, family and friends complain that they never see you anymore, or your boss notices you’re not finishing projects on time.

“If exercise becomes so all-consuming that you can’t interrupt your workout to go on vacation – you have to exercise when the plane is taking off – then that’s a problem!”

Here are a few more signs of excessive exercise:

— Compulsively following the same exercise routine for years without missing a day

— Feeling obliged to exercise no matter what the circumstances, or feeling guilty or anxious about any lapse or reduction in activity.

— Relying on physical activity as the only means of coping with stress.

— Continuing to exercise despite illness or injury, even when advised by your doctor to take a break while you heal.

— Automatically equating exercise with eating and weight control. For instance, developing a preoccupation with having to exercise to compensate for eating.

The book includes a more extensive questionnaire for assessing exercise abuse among the general public. It also includes a chapter discussing the special circumstances of competitive athletes, a group at higher risk for excessive exercise and eating disorders.

Dr. Powers emphasizes the importance of the circumstances and context surrounding your exercise routine in determining whether it’s balanced. “When my neighbor is training for triathlons she steps up her exercise regimen,” she said. “But once the competition is over, she goes back to a more moderate routine. And if she hurts something while she’s training, she does not continue running, biking or swimming.”

Dr. Powers in one of few photos with a scale. As a physician who treats many patients with eating disorders, she discourages the connection of eating with exercise and weight control.

Achieving exercise balance has become more challenging as society has shifted the focus of exercise from health to appearance – for instance, glamorizing people in entertainment or sports who maintain a low weight, Dr. Powers said. “It’s especially a real problem to figure out how to help people who adore exercise and also have an eating disorder.”

Dr. Powers recalled the first patient she met with anorexia. Even though the emaciated young girl was strapped to the bed in a pediatric intensive care unit, she was lifting her body up and down and moving her arms as much as possible within the arm restraints. She was in danger of losing her life, and she was exercising.

“You really can’t stop people from exercising unless you sedate them. It’s better to work with people to help them recognize the difference between moderation and too much exercise,” she said. “I discourage patients with eating disorders from exercising right after they eat a meal – to try to get them away from that mindset that says ‘OK, I can only eat if I exercise for half an hour.’”

“I want them to think of eating normally as one thing you do for your health, and exercising moderately is another – rather than making a compulsive connection between the two.”

Click here to visit the CDC’s “Growing Stronger” website recommended in Dr. Power’s new book.

– Story by Anne DeLotto Baier/USF Health Communications

– Photos by Eric Younghans/USF Health Media Center