Dr. Miller to SCP students: “It will change the way we practice medicine”

Students attending the College of Medicine’s 2nd Annual Scholarly Concentrations Program Student Symposium Aug. 19 got a glimpse of the future of medicine – a future where diagnosis, treatment and disease management are based on an individual’s genetic makeup.

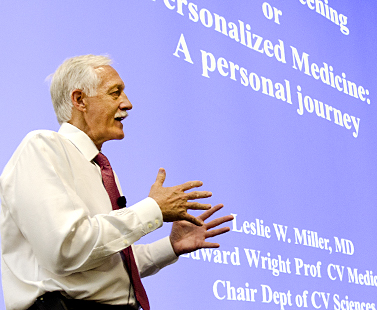

Keynote speaker Dr. Leslie Miller discussed the potential of personalized medicine to change the diagnosis and management of cardiovascular disease.

Keynote speaker Dr. Leslie Miller spoke about this journey toward personalized medicine using cardiovascular disease – his area of expertise – as an example. By 2020 the costs of cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of U.S. deaths, will triple if nothing proactive or preventive is done to head off the epidemic of the age-related disease, said Dr. Miller, the Edward C. Wright Professor of Medicine and chair of the Department of Cardiovascular Sciences.

Today, less than 10 percent of patients are managed to any degree with genomic profiling to help identify individual risk for various diseases and individual differences in drug response, Dr. Miller said. That will change as more evidence validates that an individual’s genetic profile can contribute to better health outcomes, Dr. Miller told the audience of aspiring young physicians.

A recent large survey of cardiologists indicated three-fourths recognize the “great potential” of genomics to usher in a revolution in personalized healthcare and disease prevention, he added. “They understand the power of being able to pick the right drug and the right dose, of identifying disease markers and developing new targets for drugs and other treatments.”

Dr. Miller emphasized that genetic profiling alone is not enough. Personalized medicine must encompass an understanding of how gene variations linked to a specific disease interact with epidemiological and environmental factors.

He foresees the day when genomics are able to more precisely identify at an early age those at highest risk for diseases like atherosclerosis, congestive heart failure, hypertension and diabetes, so that tailored interventions can be started to prevent or delay the disease.

“It’s going to change the way we practice medicine,” he said.

One application of personalized medicine already under investigation is whether a genetic-based approach could optimize the dosing of a drug for individual patients, thereby minimizing dangerous complications and improving effectiveness and safety.

For instance, Dr. Miller said, the National Institutes of Health has launched a 1,200-patient randomized-controlled trial comparing outcomes of one group of patients given warfarin based on standard clinical factors (like age, weight gender) and another group administered the anticoagulant based on clinical factors and genotype. Warfarin, or Coumadin, the most commonly prescribed blood-thinning drug, is challenging for physicians to prescribe because one patient may need 20 times more of the drug than another. If the starting dose is too high, serious bleeding could occur; if it’s too low the patient may suffer a blood clot leading to a heart attack, stroke or even death.

The NIH prospective trial follows a retrospective pilot study showing that dosing warfarin with the addition of pharmacogenomic data to help pinpoint a patient’s risk of significant bleeding reduced adverse bleeding episodes by 30 percent over six months, Dr. Miller said.

The symposium showcased the work of students in the College of Medicine’s Scholarly Concencentrations Program.

This year’s symposium showcased the research and scholarly work of more than 20 medical students. Their presentations featured a wide range of topics centered on improving health outcomes.

Five years ago, the Scholarly Concentrations Program provides students with opportunities for faculty-mentored scholarly concentrations in areas of special interest such as business and entrepreneurship in medicine, health disparities, medical education or research. The program’s popularity continues to grow, with approximately 80 percent of USF medical students signed up for one of the 10 concentrations now offered.

“When I speak to applicants, one of the biggest draws of this medical school is our developed scholarly concentrations program,” said Frazier Stevenson, MD, associate dean for undergraduate medical education. “The program is absolutely critical to our efforts to inspire students’ individual passions in medical education and to advance scholarship. Scholarhip is not just research; it’s taking an inquiry-based approach to anything you do.”

Story by Anne DeLotto Baier, and photos by Eric Younghans, USF Health Communcations