An Idea Whose Time Had Come: Florida’s First College of Public Health

This story originally published on July 15, 2015 in observance of the COPH’s 30th anniversary celebration.

“USF was chosen as the place for Florida’s College of Public Health,” Dr. Peter Levin wrote in 1984, “because of the broad base of knowledge found in the many colleges of the University and the unique Tampa location.”

Levin, the college’s first dean, expounded further, noting that not only faculty from the colleges of medicine and nursing, but from business, education, engineering, natural sciences and social sciences were “key to the development of the college.”

Three decades of growth and innumerable success stories later, former Fla. Rep. Samuel P. Bell III shed more light on the founding of COPH.

Like many created entities of any kind, it all started with one person’s idea and another person’s decision to act on it.

The idea person was Robert Hamlin, a graduate of the Harvard University College of Public Health. He brought his idea to Bell, dubbed “the godfather of the college” by Charles Mahan, another founder who was COPH dean from 1995 to 2002.

“He had retired to Florida and realized that there was not a college of public health in Florida,” Bell recalled of Hamlin. “He contacted my staff director, John Phelps, with the idea, and John and I discussed the idea and decided that we should pursue the project. When we began the effort, we discovered that there had not been a college of a public health created anywhere in the country for more than 20 years, and most emphasis was on clinical health.

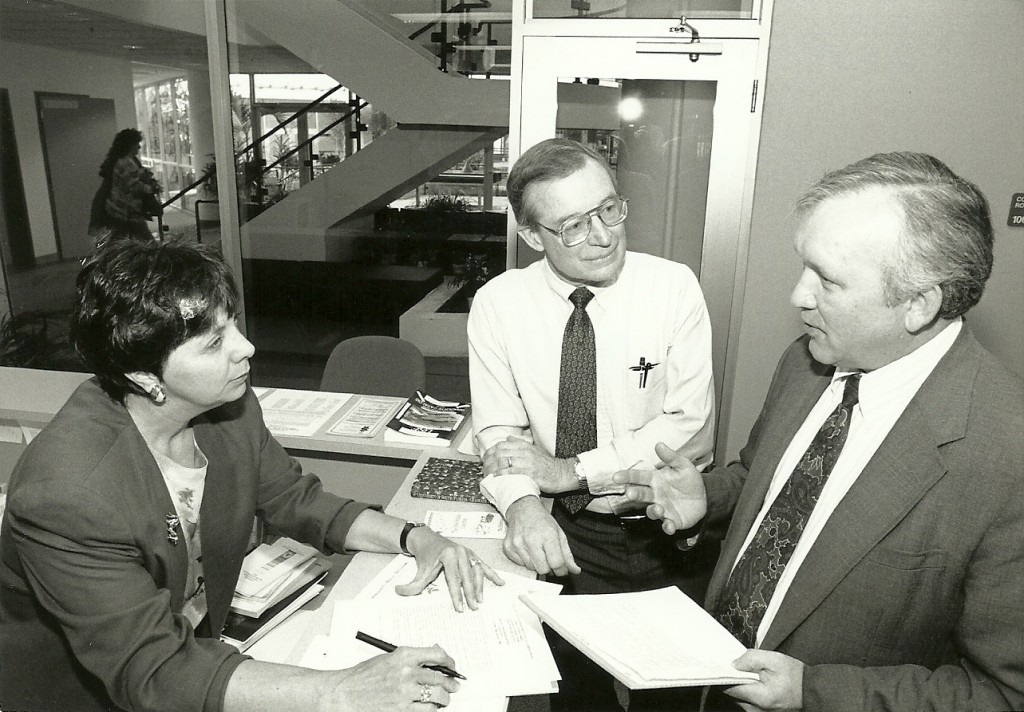

From left: Dr. Donna Petersen, dean of the USF College of Public Health, the late Robert Hamlin and Rep. Sam Bell, “the godfather of COPH.”

“As a member of the Florida Legislature, I could see the results of public health problems – mental health issues, alcoholism, child abuse, heart attack and stroke brought on by lack of exercise and obesity, infant mortality, etc. – yet there was no focus to address these issues. In addition,” Bell said, “there was a shortage of trained public health workers as problems grew and population increased.”

Where to establish the college as a physical entity turned out to be fairly obvious. Logic dictated that the state’s first college of public health had to be part of a public university that had a medical school and was located in an urban area, and USF was the only institution in the state that met all three requirements.

“There was no bill,” Bell said of the necessary legislative action that followed. “The college was first created by a line item in the state appropriation. Of course, we had to work the proposal through the Board of Regents and the USF administration.”

All of it moved with surprising quickness and ease, he said, underscoring an idea whose time had come. Naturally, it didn’t hurt that its biggest proponent was in prime position to do it the most good.

“The College’s success must first recognize the man who made it all possible,” said Dr. Heather Stockwell, the first faculty hire in the college’s Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics.

“Without Sam Bell,” she said, “there would be no COPH. Before our college was formed, there were no schools of public health in Florida. It was through the vision and leadership of Sam Bell that our college was formed and its funding secured in its early years so that it could grow and develop into the College we are all so proud of today!”

From left: Dr. Martha Coulter, Dr. Heather Stockwell and Dr. Peter Levin, first dean of COPH, ca. 1988.

“Sam Bell was absolutely committed to the idea that there needed to be a strong college of public health in this state,” Dr. Martha Coulter agreed. “He single-handedly got absolute support for us from the state legislature, so that we were not dependent completely on federal funds and training grants.”

“There was not much opposition to the effort,” Bell said. “It really flew under the radar. I was in leadership during all of this time and was chair of the appropriations committee in the House for the years 1985 through 1988, for four sessions. Before that, I had chaired the rules committee and was majority leader, so I was in a position to get support. After the College was initially approved, I was able to guide funding.”

If founding the college had seemed relatively easy, running it in the early days was not. Being the only college of public health in Florida created a heavy work load at the same time it underscored the demand for what a college of public health delivers.

The first year, Coulter and the other two faculty members in the Department of Community and Family Health traveled regularly to teach at the Florida Department of Health offices in Tallahassee and at USF-Sarasota, as well as in Tampa, said Coulter. There simply was no one else to do the job.

From left: Jennifer Harrell, filmmaker and documentarian Frederick Wiseman, Dr. Marti Coulter and the late James Harrell in an undated photo. The Harrell Center is named for Harrell and his wife, Jennifer.

“Of course, this was before you could take things online,” she said, “and it certainly was a lot easier for us to go there than for all of them to come here.”

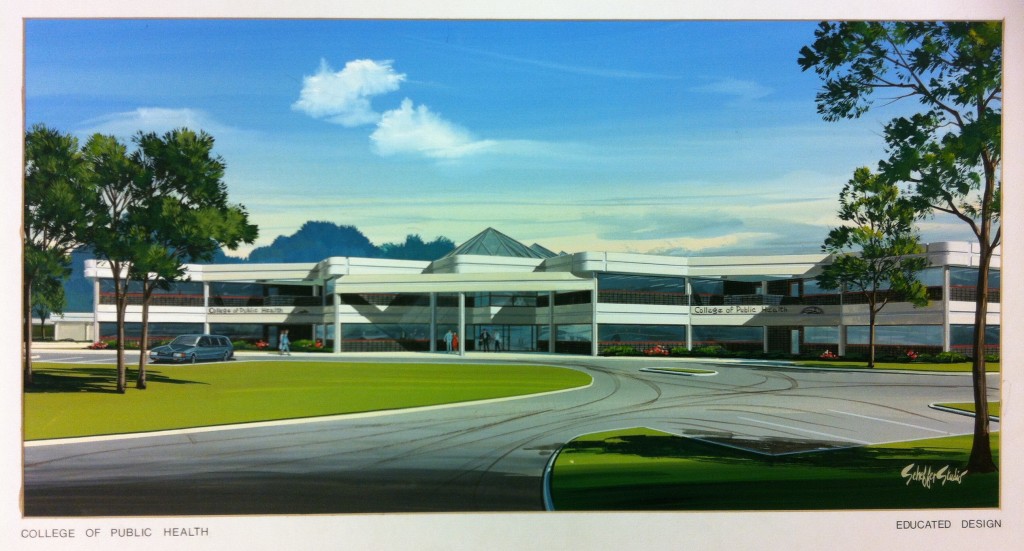

Simply finding space was another challenge. Originally housed on the first floor of the present Continuing Education building, the fledgling college wouldn’t see its own building for another seven years.

Community and Family Health had a particularly hard time finding a permanent home, Coulter said. It would reside alongside the college’s other departments in the present Continuing Education building, then move to the first floor of the University Professional Center, then find space in the Florida Mental Health Institute (now Behavioral and Community Sciences) building.

“I had to bend my head down to get into the attic to get into my office,” recalled Dr. Paul Leaverton, first chair of the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics.

“Then we took over the auditorium. It used to be a basketball auditorium – just wherever we could find room, and that was where we were ’til ’91, when we moved into this building. We kept moving around in funny little quarters, so this building was really nice – and it still is.”

A royal opening

Almost everyone expects fanfare at any major debut, the opening of a new building at a major university posing no exception, but probably no one expected the kind of pomp and circumstance that played at the USF College of Public Health’s opening of its own building in 1991.

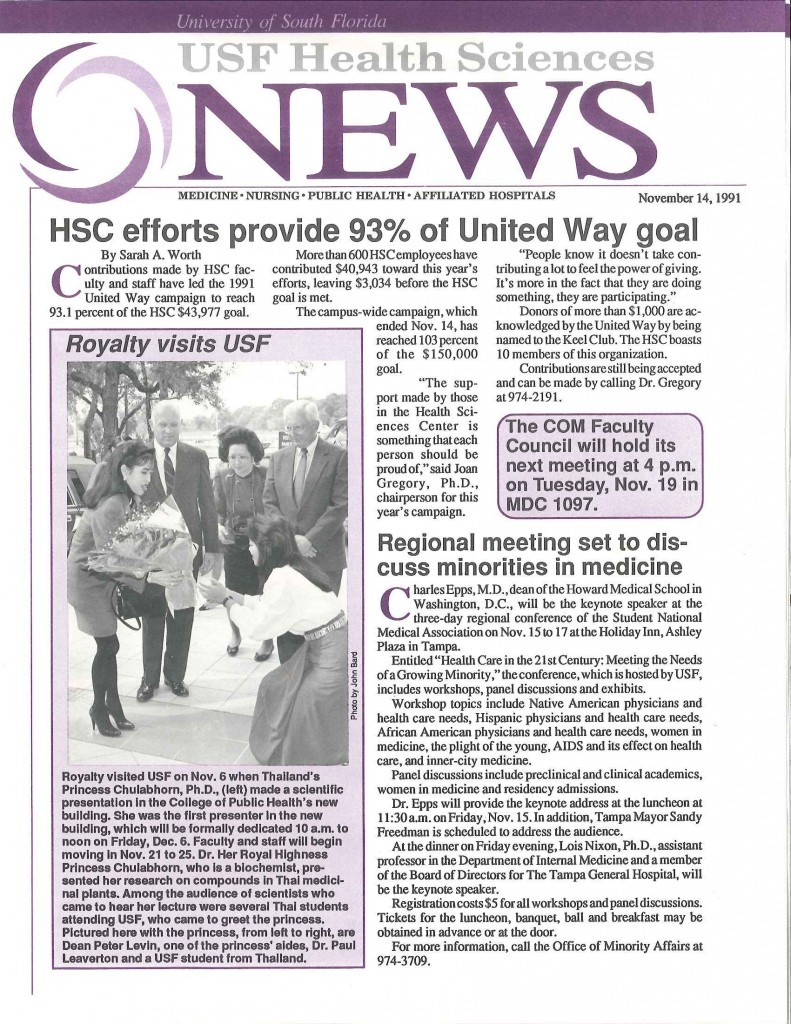

A month before the building’s official dedication, two weeks before faculty and staff even began moving in, the first lecture was delivered by a scientist, and yet the affair was literally regal.

With an entourage of attendants by her side, Professor Dr. Her Royal Highness Princess Chulabhorn of Thailand, a biochemist, arrived in a police-escorted motorcade of limousines to speak about her research on medicinal plants.

Leaverton talked recently about how the building’s unusual opening came to pass.

“In the late ’80s, I had done a lot of work in Thailand with NIH and Thai scientists on the epidemiology of aplastic anemia,” Leaverton said.

Thailand had an unusually high rate of the rare but serious blood disorder, Leaverton said, and the group set out to investigate why.

“My colleague over there was probably the top scientist in Thailand. He was a really good medical scientist,” he said, “and he was also the king’s doctor.”

The king was a believer in education, Leaverton said, and his four children eagerly shared that belief. All earned advanced degrees, and two earned doctorates. Leaverton’s Thai counterpart was a friend of Princess Chulabhorn’s, having done post-graduate work with him in Germany.

“So even though she’s a multimillionaire as the king’s daughter, they took it to heart that they should give back to the community. So she got an education in science and directs her own research institute, mostly in cancer.

“I had not met her, but I had heard of her and knew she liked to give lectures occasionally, so I asked my friend, ‘Do you think she’d ever like to give a lecture at USF?’ He said, ‘I’ll ask her.’

A short time later, back at USF and ready to re-settle into his routine, Leaverton had a surprise waiting for him.

“The next thing I know, my phone’s ringing, and it’s the ambassador from Thailand asking if I’d like the princess to speak at USF.”

The answer was yes, and the ambassador personally flew down from Washington to make the arrangements.

“He sounded pretty upset,” Leaverton said, “but they have to handle the royal family with kid gloves. Turned out he was a wonderful man, and he came down a couple of times. We had to meet with the mayor of Tampa and the chief of police to make sure the princess got a motorcade from the airport to her hotel – she took over three floors at the new Wyndham – and from her hotel to USF and back again, no stopping at red lights. So it was quite a show.

“The building wasn’t scheduled to open until December, but to make her schedule, she could only come in November, so the dean opened the building just to accommodate her, which I thought was nice.

News story on Thailand’s Princess Chulabhorn’s royal visit for the COPH opening, November 1991. Pictured with the princess (left) are Drs. Peter Levin (second from left) and Paul Leaverton, who watch as a student from Thailand extends a greeting.

“It was a packed audience. She gave a very technical lecture that no one understood except the biochemists, but it was a big show, and we got to have lunch with the president of the university. It was a royal opening for the college.”

When the college first opened for classes, Leaverton said, a few students were admitted even before the departments were created. After they were created, the departments didn’t last long initially.

Dean Levin created the initial four of COPH’s present five departments and recruited four professors from other institutions to chair them.

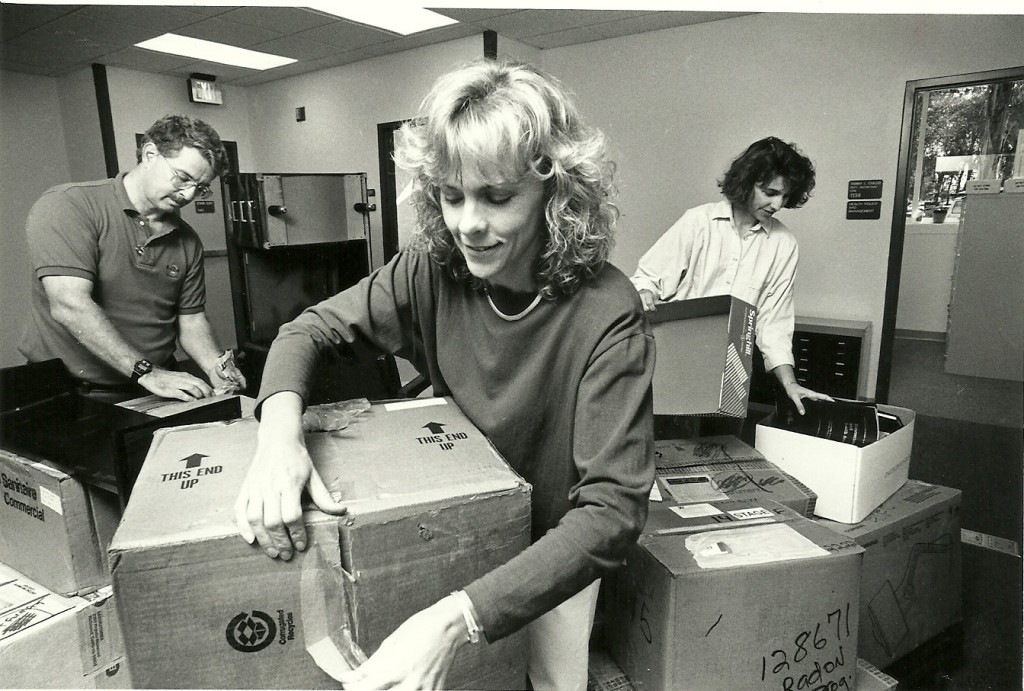

From left: Dennis Werner, senior research coordinator, Jan Marshburn, research assistant, and Lesley Bateman, PR and development coordinator, move into the new COPH building in November 1991.

Leaverton was brought in from the National Institutes of Health, and before that, the University of Iowa, to head Epidemiology and Biostatistics. Dr. Stewart Brooks would leave the University of Cincinnati to lead Environmental and Occupational Health. Dr. Stan Graven came from the University of Missouri to direct Community and Family Health. Dr. Tom Chirikos from Ohio State University would take the reins in Health Policy and Management.

“In early ’85,” Leaverton recalled, “the dean got to thinking maybe we didn’t need departments. We could just follow what he called the Texas model – no departments, just one big happy family. But the four chairs who had been recruited to be chairmen of departments objected mightily, and besides, I tried to convince the dean, students tend to think of themselves along discipline lines anyway, whether you call them departments or not. So he relented and re-created the four departments.”

Typical of the new departments, “Epi and Biostats,” as Leaverton calls it, consisted of two people. He and Stockwell were it for the time being, but that was about to change, although maybe not as quickly as they would have liked.

“The legislature was wonderfully generous,” Leaverton said. “They gave us a lot of tenure-track lines, almost unheard of in the creation of a new school. As chairman of Epi and Biostats, I had six tenure-track lines. Two of them were filled by Dr. Stockwell and me, but we had to recruit for the other four.

“Dr. Stockwell and I both had pretty high standards – she had been at Hopkins. We had a file of about 30 people. We rejected all of them. We didn’t think they were good enough to be on our faculty.

“So we had to start the recruiting process all over again, and she and I did all the teaching for that first year, because we were a two-person faculty. We did have a few adjuncts, maybe, here and there, and we eventually filled the faculty positions for the next year.”

Leaverton chaired the department until 1995, then remained as a professor for another six years. He retired as an emeritus professor in 2001.

Memories

The founders and early leaders of COPH have more memories than just those that deal with the college’s inception and its early operation, more memories than space could ever allow, including a few on the lighter side.

“When she was president of the university, she knew everybody on campus,” Coulter recalled of Betty Castor, “and when I got the funding to start the Harrell Center, I was walking across the campus behind the administration building, and she was walking back to her office from somewhere. She saw me all the way across the grounds and yelled out, ‘Hi, moneybags!’

Sam Bell and Betty Castor, former USF president and Florida Secretary of Education, at the COPH 25th anniversary gala, December 2009.

“She knew everybody and supported everybody, and no matter that I was an associate professor in the College of Public Health, she knew.”

“I recall conducting a final exam in epidemiology one evening in which two unusual events occurred,” said Leaverton. “First, a student came to me in obvious pain. She had accidentally put the wrong kind of eye drops in her eyes, which were nearly swollen shut. Okay, she was excused.

“Then, another lady went into labor. We called 911 and sent her to the hospital. It turned out to be a false alarm – she delivered two weeks later. Maybe my exams were too frightening.”

“Being a fan of Chevy Chase and SNL, especially his take-offs on the clumsiness of President Gerald Ford, I purposely stumbled up the auditorium stairs and fell against the podium on the stage, scattering papers everywhere,” Mahan recalled. “This was at one of our graduation convocations. Instead of the audience laughing at my parody of Chevy, they all thought it was real and rushed to the stage to help me – very embarrassing! I think it’s funny now, but I have a very bizarre sense of humor.”

The particulars vary from person to person, but the size, scope and overall success of the college are unanimous themes for the people who were there in its earliest days. In one way or another, all said they could not have foreseen in 1984 what it is on its 30th anniversary.

“I don’t think we could have imagined,” Coulter said, “the ability to move as strongly as it has in the direction of being a research one university – USF as a whole and the College of Public Health as a leader in that regard. I don’t think we quite envisioned it that way. That has been very exciting.

“Also, the expansion of the whole global health department, the global health focus, and the ability to do international public health work with researchers that are in the global health unit. That really hadn’t been anticipated,” she said.

“I think Donna Petersen coming here was a huge milestone,” she added. “I think she is absolutely extraordinary. Without Donna’s leadership, we could not have gone as far as we’ve gone. She’s given us a lot of support for community-based research, and that’s been critical in terms of the direction that we’ve gone.”

“I’m very pleased with how well our students have done,” Leaverton said. “It’s kind of shocking, in a way. As I look back, we must have organized the curriculum pretty well, Heather [Stockwell] and I. We had to basically design it from scratch. We set up some pretty good courses, and they essentially stayed the same for a long time. We had some good faculty who kept the standards high.

COPH student Sherri Berger as a model for a National Public Health Week poster, March 1996. She now is chief operating officer at the Centers for Disease Control.

“I actually saw some memos that said, ‘Don’t take Epi and Biostats at the same time, it’s too hard. You have to take them separately,’” Leaverton said. “Sometimes I would take some pride in that. We never made soft courses. Our courses were tough.”

Past, Future and Present

The few shortcomings the college’s founders can think of actually only further reflect the college’s success.

“If I could change one thing,” Stockwell said, “it would be to have a much larger building. The college’s rapid growth has resulted in a need for more space. Maybe we could add a floor?”

“Our beautiful building should have been built to be able to add additional stories,” Mahan concurred.

For Leaverton, it would be an epidemiology laboratory, something he said he and Dr. Doug Schocken, a cardiology professor, tried twice to get funded by NIH.

“If I could do that over, I would pursue that even more vigorously. But we tried,” he said.

Mahan said he sees the college’s future dependent upon “a stronger marriage” between the college and the state and local health departments.

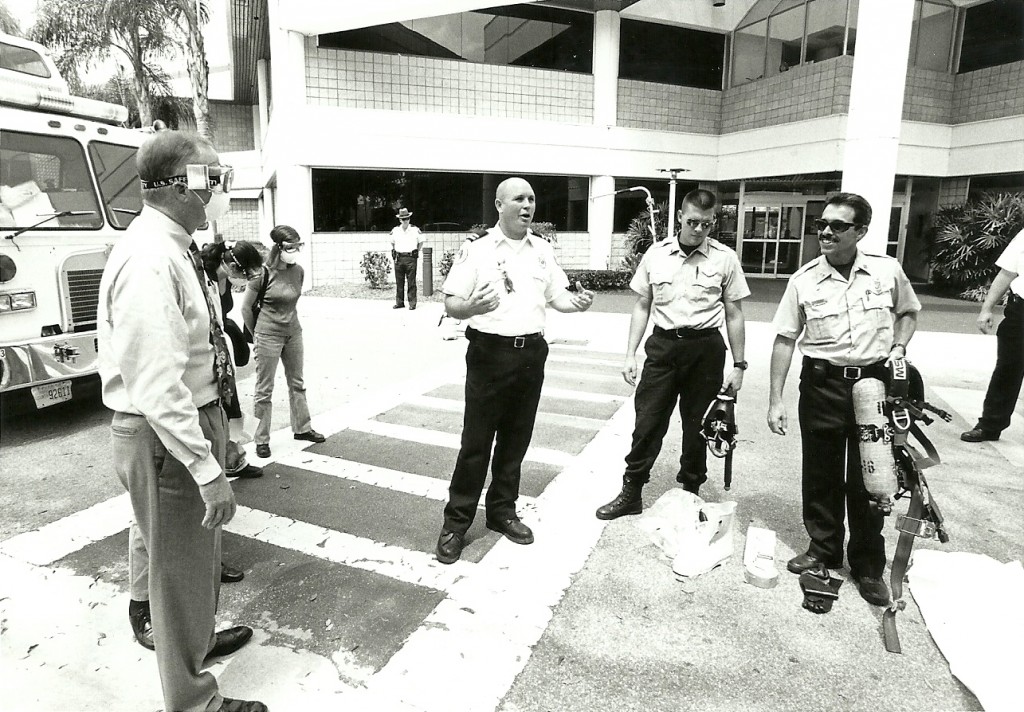

Former COPH Dean Dr. Charles Mahan (above left, below right) participates in an exercise with the Hillsborough County Fire Rescue Hazardous Materials Unit, April 2000.

“What if you got your medical degree or nursing degree but never saw a patient and never went into a hospital? Well, why are we giving people public health degrees, and they never set foot in a health department, and they don’t work in the community, which is where the problems are?”

Mahan believes that national accreditation of health departments should be as universal as accreditation for colleges and universities, and that closing the gap between public health education and practice is the way to achieve it. COPH would help a health department earn accreditation, with the understanding that once it became accredited, it would become an “official outpost of the USF College of Public Health.”

“I hope the emphasis on a strong research program will continue,” Leaverton said. “Public health programs need to be based upon sound science, of course. I hope that never changes.”

“What I would like to see the college do is continue on the path that it’s on in terms of really being a leader in the country in community-based research,” Coulter said, “increasing its role as an intermediary between research and practice, and having a committed sense of responsibility to community service providers.”

“Over the next five years,” Stockwell said, “I think – or at least I hope – that public health in general will focus on a positive approach to health, not just disease prevention but improving the quality of health and health maintenance for all our citizens. To do this there will need to be a strong interdisciplinary approach to developing strategies that focus on primary prevention and sustainability at the community level.

“I think our college is uniquely positioned to address these issues,” she said. Its interdisciplinary educational focus positions it as a leader in public health education, and our emphasis on the development of high-quality, collaborative, community-based research seeks to provide critical information to policy makers to address current and future public health concerns locally, nationally and internationally.”

From left: Susan Webb and Drs. Michael Reid and Phillip Marty establish the Public Health Leadership Institute with a grant from the CDC and ASPH, January 1995.

Stockwell remained with COPH until 2014, when she retired as professor emerita.

But between all the memories of COPH’s beginnings, all its history, successes, scarce shortcomings and envisioned futures stands the here and now.

“If imitation is the greatest form of flattery,” he said, “then we should be flattered, because every university in the state wants a college of public health.

“The College is having impact around the world. I had thought it would be a mecca for public health in Florida and a source of information and advice for state decision-makers. It has done that and much more. We now have graduates working on every continent. Our faculty are internationally recognized. Our students are studying and doing internships around the world. We are attracting major grants, and the research continues to grow.

“I am very proud of what the College has become and what it has done to touch lives around the world,” the college’s “godfather” concluded.

“It has far exceeded my hopes and expectations.”

The USF College of Public Health solves global problems and creates conditions that allow every person the right to universal health and well-being. Make a gift today and help the COPH to advance the public’s health for the next 30 years and beyond.

Story by David Brothers, USF College of Public Health; photos courtesy of COPH and various faculty.

Related media:

30th anniversary website