Dr. Katherine Drabiak authors paper on ethics, efficacy of mitochondrial replacement therapy

Dr. Katherine Drabiak, a USF College of Public Health assistant professor of bioethics and genomics, recently published the article “Emerging Governance of Mitochondrial Replacement Therapy: Assessing Coherence Between Scientific Evidence and Policy Outcomes,” in the DePaul Journal of Health Care Law.

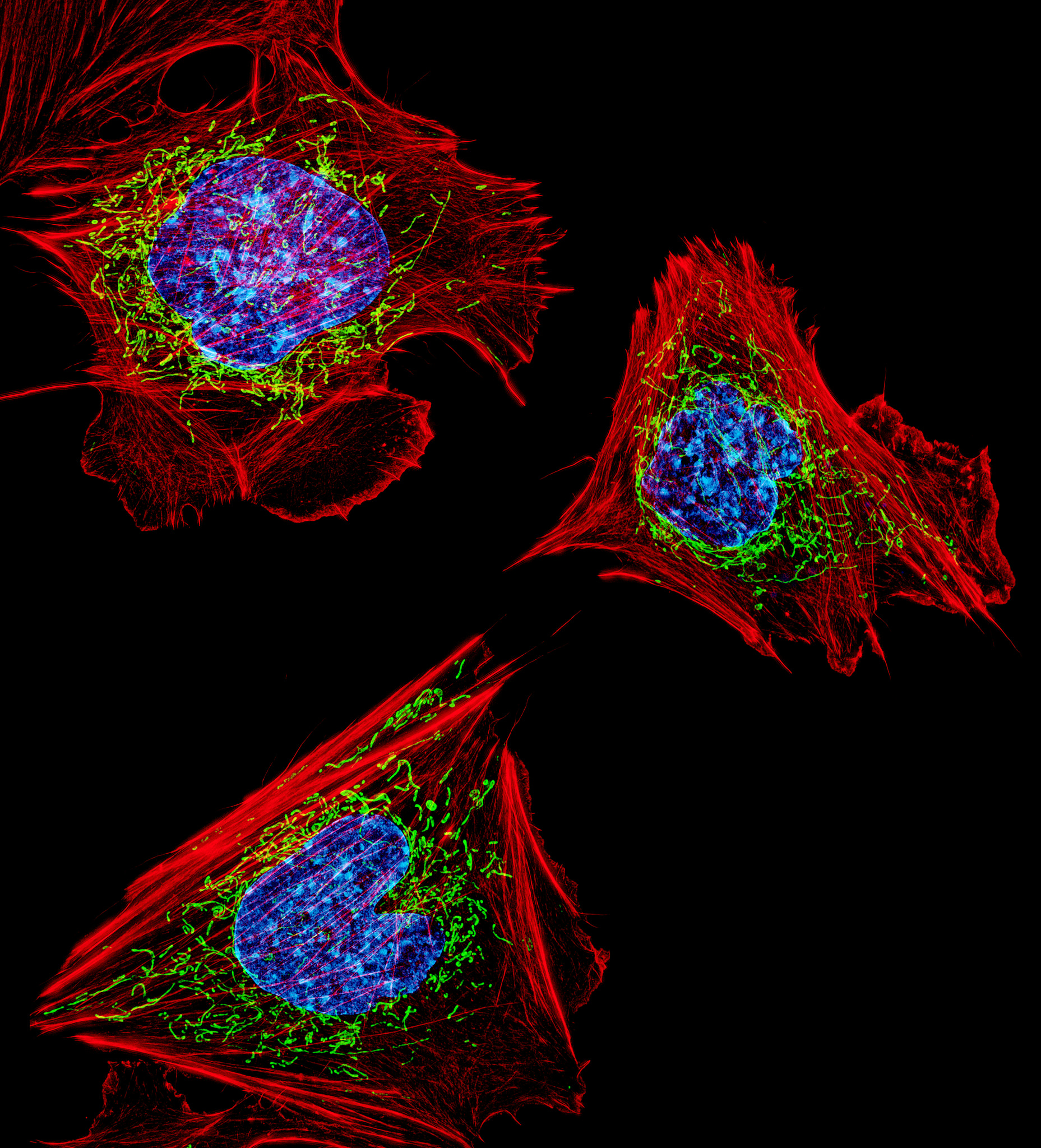

Mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT) is an experimental procedure in which nuclear DNA from a mother’s egg or fertilized zygote is transferred into a donor’s egg or fertilized zygote. In theory it is used to reduce the risk of maternal transmission of mitochondrial DNA disease. (Mitochondria are cells that supply energy to the body; mitochondrial disease can have deleterious effects on those parts of the body requiring great amounts of energy—things like the heart, brain and lungs.)

“There are a lot of ethical issues here,” emphasized Drabiak, who is also an attorney.

Katherine Drabiak, JD, an attorney and assistant professor of bioethics and genomics in the USF COPH. (Photo by Anna Mayor)

For starters, the procedure is highly experimental and far from a surefire cure for inherited mitochondrial disease.

“When you take out nuclear DNA from the mom, some of the damaged mitochondrial DNA is transferred along with it,” noted Drabiak. “Those cells can take over, and they can do so in an unpredictable way.”

Drabiak points to research showing that the maternal transmission of mitochondrial disease is rare, affecting just one in 10,000 individuals. “Failing to recognize this can skew public perception.”

What’s more, MRT is expensive, costing about $100,000.

“The potential cost is high, and it might not even create the healthy baby couples are looking for,” commented Drabiak.

And those problems are just the tip of the iceberg.

Mitochondrial cells. (Photo source Google Images)

Because MRT modifies germlines (e.g., future genetic lineage) it may be illegal as well as unethical. Drabiak notes that the United Nations, the Council of Europe and some nations have laws explicitly prohibiting this practice. However, in 2016 the United Kingdom was one of the first countries to allow “cautious use” of MRT. “Right now there is a federal law in place preventing the FDA from using federal money for research that changes the germline,” said Drabiak. “But I don’t see that as a permanent barrier.”

Another emerging complication? Using MRT to treat infertility.

Drabiak notes that the unproven MRT-as-fertility-treatment is already being advertised in parts of Europe, and even one doctor here in the U.S. made headlines when he traveled to Mexico to perform the procedure for a Jordanian couple.

“Infertility is such a big issue for so many couples,” said Drabiak. “But the assisted-reproductive-technology industry is largely unregulated. There is a lot of hype and a lot of marketing to desperate couples who want a genetically related child. Many new techniques like MRT get swept into practice with not a lot of oversight. I’m concerned about the transparency. Where’s the evidence? Where’s the science? And do the laws match up? An infertile couple might see a headline about something like MRT and think it is the answer to their prayers, but is it?”

The bottom line, says Drabiak, is buyer beware. Some of the science suggests this procedure could create new serious health risks for the child, such as a risk of cancer or premature aging.

“In the future, I think MRT will be used more and more. Couples need to be cognizant of how loosely this industry is regulated. Google the terminology. See what the FDA says on its website. See what the claims are about safety and efficacy. And in the end, take whatever claims these clinics are marketing as just that—advertisements.”

Story by Donna Campisano, USF College of Public Health