COPH visiting professor studies factors influencing youth violence

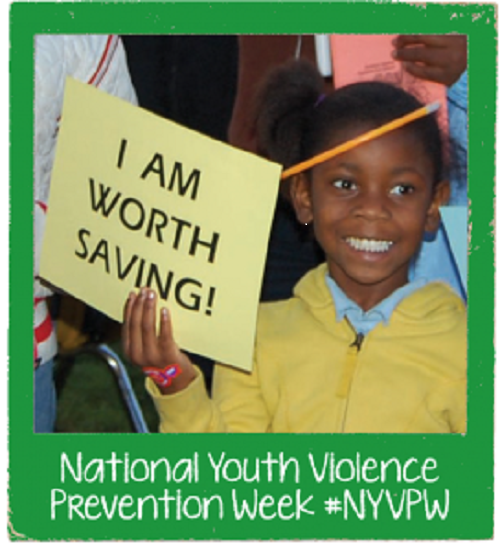

National Youth Violence Prevention Week is April 8-12

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

- Every day in this country, 13 young people are victims of a homicide.

- Nearly 33 percent of high school kids have been in a physical fight in the last year.

- Roughly 16 percent of high schoolers have carried a weapon on one or more days in a 30-day period.

In his role as research faculty at the Harrell Center for the Study of Family Violence, Dr. Abraham Salinas-Miranda, a USF College of Public Health (COPH) visiting research scholar and COPH alumnus, has been examining some of the determinants of juvenile violence.

The mission of the Harrell Center is to provide education, training, research and advocacy on family violence, as well as other forms of violence, such as juvenile violence and community violence. The Harrell Center serves as a bridge between academia and the community, and frequently engages in collaborative projects with community organizations tackling multiple forms of violence in Tampa Bay.

Salinas and his Harrell Center colleagues have been involved in Safe and Sound Hillsborough, a violence-prevention collaborative in Hillsborough County that addresses violence in the community. Some of the partners in the collaborative include the county’s public defenders, school board, health department and law enforcement, among others. The former director of the Harrell Center, Dr. Martha Coulter (Salinas’ former mentor), helped develope these efforts in collaboration with the community partners and also evaluated them.

After Safe and Sound Hillsborough surveyed a large majority of the public schools in Hillsborough County (more than 27,000 students took part), Salinas and other researchers took the dataset and have continued to analyze it, testing multiple hypotheses of theoretical and practical importance for juvenile violence prevention.

“The idea,” said Salinas, “is to get additional insight beyond the report, specifically information that can potentially elucidate pathways for [juvenile violence] intervention.”

In analyzing the data, Salinas and his colleagues have been able to pinpoint some of the factors that can help protect youth against violence.

Number one is what Salinas calls “social cohesion.”

“This is social connectedness,” explained Salinas. “Put another way, it’s how well people in the community know and support each other. We found the greater the social cohesion, the higher the perceived safety among youth. Several studies have indicated that perceived school and neighborhood safety is associated with lower crime rates and is an important indicator of juvenile and community violence exposure. We have found that social cohesion, particularly neighborhood social cohesion, is a protective factor against violence. And not just for juveniles, but for everyone overall. That’s because the more a community knows each other, the more likely they are to trust each other, intervene and help each other.”

Other protective factors include having a supportive adult at home or school and neighborhood walkability (for example, perceiving that is safe to walk at night in a neighborhood).

Salinas and others at the Harrell Center are also involved in mining information from another large sample-size database, this one involving the 2016/2017 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), a project directed by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau, which is funded by the federal government.

“We’re looking, specifically, at how adverse childhood experiences are connected to bullying, which is really just another expression of juvenile violence,” commented Salinas. “Our first analysis of the data shows that children who are victims of bullying are at increased odds of reporting adverse childhood experiences.”

A possible area of future Harrell Center research, says Salinas, is taking that same NSCH data and examining what role mental health—specifically depression—plays in bullying victimization and perpetration. This new project, which will apply structural equation modeling and mediation analysis, is currently being developed by Dr. Salinas, Dr. Nicholas Thomas (a Harrell Center postdoctoral fellow), Dr. Russell Kirby, Dr. Ronee Wilson, and a group of doctoral and master students.

“There are some studies that show children who are bullied are more likely to develop depression in the future,” added Salinas. “And there are other studies that show that children who are depressed are more likely to be victims of bullying. But why? Does one’s mental health affect how one copes? We’re interested in finding out how depression and bullying interact and whether one influences the other.”

Story by Donna Campisano, USF College of Public Health