COPH and University of Pittsburgh partner on Florida measles simulator

April 22-28 is World Immunization Week

Take one student with measles and plunk him or her down in an area where measles vaccination rates have dropped 10 percent overall.

What would happen?

It’s a question Dr. Karen Liller, a USF COPH professor of community and family health, posed to Dr. Mark Roberts, a professor and chair at the University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health and director of the university’s Public Health Dynamics Laboratory.

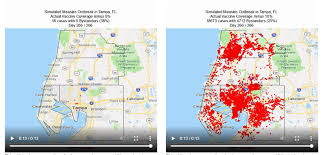

Roberts and his team developed a simulator called FRED (Framework for Reconstructing Epidemiological Dynamics). FRED takes vaccination rates—both real and hypothetical—and shows possible outbreaks following the introduction of a single measles case in a selected U.S. city.

For the Florida experiment, Roberts input data collected by Liller from the Florida Department of Health school immunization records. The simulator showed what would happen over a nine-month period if one student with measles went about life in an area where current vaccination rates held steady—and then in an area where the rates dropped by 10 percent.

When the vaccination rate dipped, the increase in cases—which the simulator showed spreading wildly in the first few months before dropping off—was dramatic.

Not to mention alarming.

“You don’t have to have immunization rates drop that much to have a serious public health issue,” said Liller, who is also director of the Activist Lab, a COPH initiative that provides students with opportunities to advocate for public health issues and become active in local, state and national government. “The cases just balloon.”

And the reason they balloon, say experts, is the decrease in what’s called “herd immunity.”

The theory behind herd immunity is this: The more people who are immunized against a disease, the more a community is protected. When most people are vaccinated, outbreaks can’t spread easily. Germs peter out because they can’t take hold, thus providing “herd immunity.”

Having a strong “herd immunity” is particularly important to those people who can’t be immunized—for example, newborns and those immunosuppressed.

“Numbers are abstract,” explains Liller, who, along with the Activist Lab, may use the data to lobby state legislators for tougher immunization policies. “It’s hard for people to put faces to numbers. But this simulator gives people a very good visual representation of the enormity of what would happen. Interestingly, it doesn’t show you all at once what would occur. It shows you how the disease progresses in real time, over days, weeks and months.”

Roberts notes that the FRED platform can be used to illustrate the spread of a wide variety of diseases, not just measles.

“It’s flexible,” said Roberts. “We can recreate what would happen with multiple different diseases and conditions. In fact, we’ve put in place a simplistic version for cardiovascular disease in Allegheny County [Pennsylvania] and we are currently under contract from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to incorporate opioid-use disorders.”

“This simulator is an amazing tool,” commented Liller. “It gives you an idea of how huge outbreaks can be incredibly taxing on our public health system.”

To see the FRED simulator in action, click here.

Story by Donna Campisano, USF College of Public Health