USF Health study links Aβ-activated enzyme cofilin with the toxic tau tangles in major neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease

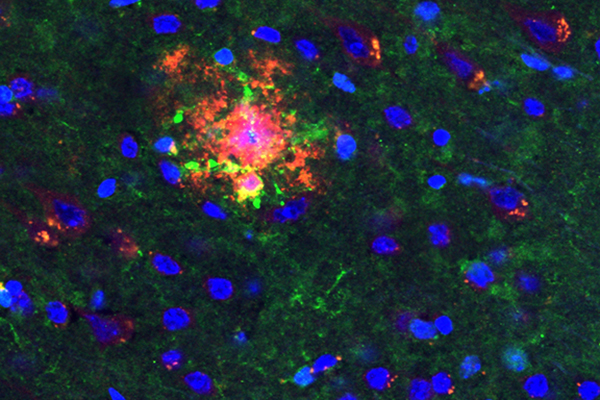

Neurofibrillary tau tangles (stained red) are one of the two major brain lesions of Alzheimer’s disease. Blue fluorescent stain (DAPI) depicts the nerve cell nuclei.

TAMPA, Fla. — The two primary hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease are clumps of sticky amyloid-beta (Aβ) protein fragments known as amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles of a protein called tau. Abnormal accumulations of both proteins are needed to drive the death of brain cells, or neurons. But scientists still have a lot to learn about how amyloid impacts tau to promote widespread neurotoxicity, which destroys cognitive abilities like thinking, remembering and reasoning in patients with Alzheimer’s.

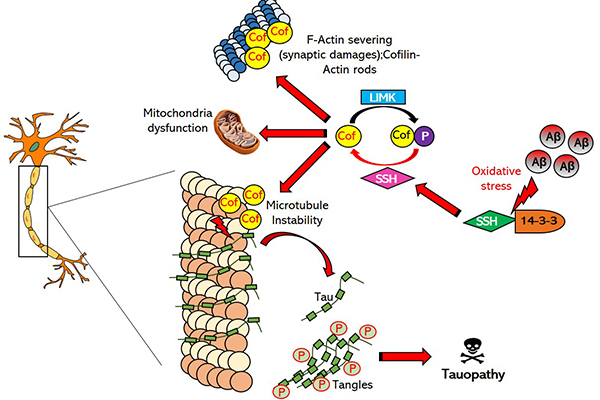

While investigating the molecular relationship between amyloid and tau, University of South Florida neuroscientists discovered that the Aβ-activated enzyme cofilin plays an essential intermediary role in worsening tau pathology.

Their latest preclinical study was reported March 22, 2019 in Communications Biology.

The research introduces a new twist on the traditional view that adding phosphates to tau (known as phosphorylation) is the most important early event in tau’s detachment from brain cell-supporting microtubules and its subsequent build-up into neurofibrillary tangles. These toxic tau tangles disrupt brain cells’ ability to communicate, eventually killing them.

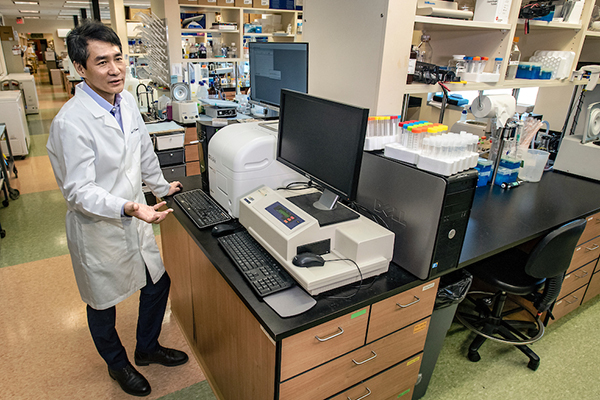

David Kang, PhD, director of basic research at the Byrd Alzheimer’s Center, USF Health Neuroscience Institute, was senior author of the Communications Biology paper.

“We identified for the first time that cofilin binds to microtubules at the expense of tau – essentially kicking tau off the microtubules and interfering with tau-induced microtubule assembly. And that promotes tauopathy, the aggregation of tau seen in neurofibrillary tangles,” said senior author David Kang, PhD, a professor of molecular medicine at the USF Health Morsani College of Medicine and director of basic research at Byrd Alzheimer’s Center, USF Health Neuroscience Institute.

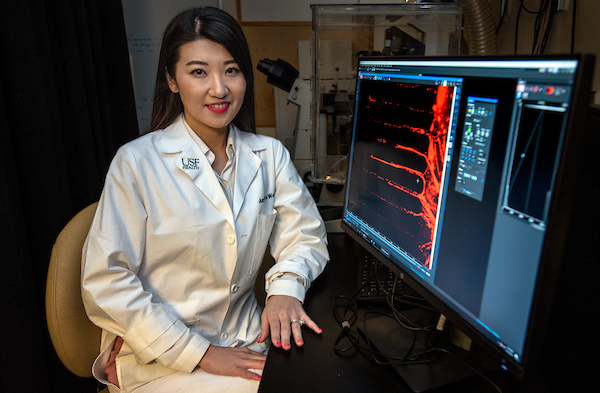

Dr. Kang also holds the Fleming Endowed Chair in Alzheimer’s Research at USF Health and is a biological scientist at James A. Haley Veterans’ Administration Hospital. Alexa Woo, PhD, assistant professor of molecular pharmacology and physiology and member of the Byrd Alzheimer’s Center, was the study’s lead author.

The study builds upon previous work at USF Health showing that Aβ activates cofilin through a protein known as Slingshot, or SSH1. Since both cofilin and tau appear to be required for Aβ neurotoxicity, in this paper the researchers probed the potential link between tau and cofilin.

The microtubules that provide structural support inside neurons were at the core of their series of experiments.

Alexa Woo, PhD, an assistant professor of molecular pharmacology and physiology at the USF Health Morsani College of Medicine, was the paper’s lead author.

Without microtubules, axons and dendrites could not assemble and maintain the elaborate, rapidly changing shapes needed for neural network communication, or signaling. Microtubules also function as highly active railways, transporting proteins, energy-producing mitochondria, organelles and other materials from the body of the brain cell to distant parts connecting it to other cells. Tau molecules are like the railroad track ties that stabilize and hold train rails (microtubules) in place.

Using a mouse model for early-stage tauopathy, Dr. Kang and his colleagues showed that Aβ-activated cofilin promotes tauopathy by displacing the tau molecules directly binding to microtubules, destabilizes microtubule dynamics, and disrupts synaptic function (neuron signaling) — all key factors in Alzheimer’s disease progression. Unactivated cofilin did not.

The researchers also demonstrated that genetically reducing cofilin helped prevent the tau aggregation leading to Alzheimer’s-like brain damage in mice.

An amyloid plaque (stained red), one of the two major brain lesions of Alzheimer’s disease, is shown here with the Aβ-activated enzyme cofilin (green) and nerve cell nuclei (blue).

“Our data suggests that cofilin kicks tau off the microtubules, a process that possibly begins even before tau phosphorylation,” Dr. Kang said. “That’s a bit of a reconfiguration of the canonical model of how the pathway leading to tauopathy works.”

Since cofilin activation is largely regulated by SSH1, an enzyme also activated by Aβ, the researchers propose that inhibiting SSH1 represents a new target for treating Alzheimer’s disease or other tauopathies. Dr. Kang’s laboratory is working with James Leahy, PhD, a USF professor of chemistry, and Yu Chen, PhD, a USF Health professor of molecular medicine, on refining several SSH1 inhibitors that show preclinical promise as drug candidates.

The research described in this Communications Biology paper was supported by grants from the VA, the NIH National Institute on Aging, and the Florida Department of Health.

Schematic of activated cofilin in tauopathy, which leads to pathological brain changes in people with Alzheimer’s disease and other major neurodegenerative disorders | Courtesy of Alexa Woo

-Photos by Allison Long, USF Health Communications and Marketing