The Department of Defense study is testing how well multifunctional prosthetic feet work for rigorous, agile maneuvers soldiers must perform on the battlefield

Whenever he leaves for the airport on vacation, Joshua Sparling carries along a bag full of legs and feet. There are different prosthetic components for running, others for swimming, bicycling or golfing, and yet another for everyday walking.

Sparling, 31, who lost his right leg to an improvised explosive device (IED) while serving as an Army sergeant in Iraq in 2005, has experienced the discomfort of prostheses not particularly well suited for his high-intensity athletic endeavors. So he was enthusiastic about enrolling in a U.S. Department of Defense-funded study at the University of South Florida School of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Sciences – traveling from Michigan to Florida to participate in the research.

The project is evaluating how well different multi-functional prosthetic feet work for rigorous and agile maneuvers soldiers must perform on the battlefield – from running and jumping to dodging, crawling and climbing.

The advanced prosthetic research involving military amputees may ultimately benefit civilian amputees with physically challenging occupations or recreational pursuits, such as firefighters, police officers, construction workers, triathletes, marathon runners or rock climbers.

“Our findings will have implications not only for the rehabilitation of soldiers who seek to stay on active duty, but also for civilians with amputations who want to participate in activities at a more intense level,” said Jason Highsmith, PhD, DPT, the USF Health assistant professor of physical therapy leading the study. The knowledge researchers gain from evaluating high-end prostheses that can help soldiers move more efficiently across war zone terrain can also be applied to developing prosthetics “for common movements like walking or jogging at a comfortable pace,” he added.

Army Staff Sgt. Brian Beem, a partcipant in the DOD-supported prosthetic research study, hoists himself over one of the many obstacles at the Walter C. Heinreich training site.

Beem races agains the clock to finish a course that pushed participants to complete the same physically-demanding maneuvers soldiers must perform on the battlefield.

The USF researchers enrolled 28 physically fit people in the DOD double-blind randomized trial. Half are soldiers and veterans who wear prostheses for below-the-knee amputations, the most common kind of lower limb loss. The other half are non-amputees from the local law enforcement SWAT team.

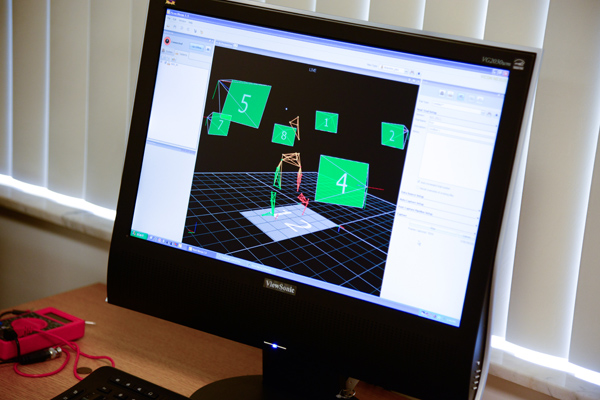

This spring, the military amputees were evaluated wearing each of three different commercially-available high-tech prostheses. The study participants were tested in USF’s Human Functional Performance Laboratory, where they walked and ran on treadmills while researchers measured performance parameters, including range of joint motion, prosthetic foot power, oxygen consumed and energy expended. At the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office training facility, the researchers evaluated obstacle course completion times, heart rates and perceived difficulty of performing such tactical maneuvers as charging up inclines, climbing ropes and slalom running requiring a combination of speed, agility and balance. Each participant was asked to rate the preferred prosthetic foot – both in the lab and in the field.

Non-amputees are presently completing the same testing. Researchers will compare the physical performance of the amputee group to the non-amputee control group, with the aim of identifying which prosthetic foot may be best suited for military applications. They expect to have results by the end of this year.

Jason Highsmith (left), PhD, DPT, assistant professor of physical therapy leading the DOD study, adjusts the oxygen mask of Joshua Sparling.

In the USF School of Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Sciences Human Functional Performance Laboratory, study participant Sparling, wearing one of the hi-tech prosthetic feet being tested, runs on a split-belt treadmill as researchers monitor his gait and various performance indicators.

Scientifically determining which prosthesis comes closest to an anatomic foot when performing battlefield maneuvers is important, Highsmith said, because a person with an amputation uses more energy than someone with a natural foot for comparable movements at the same speed.

USF’s prosthetic research has the potential to transform the lives of a growing number of young wounded warriors, like Army Staff Sgt. Brian Beem, by giving them the option of returning to active service – possibly even the war zone – if they desire and can perform the functions required by the job.

While deployed in Iraq in 2006, Beem, 35, lost his right leg below the knee following a roadside blast that claimed the life of a fellow soldier and friend. Despite the injury, he re-enlisted for the third time November 2011 at Forward Operating Base in Frontenac Afghanistan and continued to serve his country with other Calvary scouts. Beem, who calls himself a “career soldier,” now tests night-vision goggles, scopes and other devices at the Army’s Research and Development Center in Fort Belvoir, VA.

“I take it as a badge of pride that at one place I worked it took three months for my boss to figure out I was an amputee,” Beem said. “It’s easy to forget you’re ‘disabled’ when the technology we have now can make the prosthesis comparable to a fully functioning foot.”

Sparling is impressed with the latest-generation prosthetics he’s been asked to help evaluate – all integrating varying degrees of rotational, shock-absorbing and energy-returning characteristics. “The advances made to this point have been pretty amazing,” he said. “Nothing leads me to think it won’t get even better.”

Dr. Highsmith specializes in research to improve prosthetic options for those who lose limbs from traumatic injury or diseases – including soldiers and veterans reintegrating into society. He works with USF physical therapy and engineering colleagues.

USF’s Highsmith is equally impressed with the wounded warriors and veterans like Beem and Sparling who volunteered for the DOD study and push themselves to perform at levels comparable to SWAT team members without amputations.

“They’re extremely inspirational,” he said. “They’ve left parts of their bodies overseas defending our freedom… It’s personally rewarding to spend time with these heroes, hear their stories, contribute in some way to their ongoing rehabilitation, and, hopefully, we’ll find out which prosthesis works best so they can continue to stretch their limits.”

Brian Beem

Joshua Sparling

Video by Allyn DiVito, USF Health Information Systems, and photos by Eric Younghans, USF Health Communications